Hear now the tale of Iphis and Ianthe, told by the Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE -17/18 CE):

In the Phaestos region of Crete, lived a couple named Ligdus and Telethusa. Telethusa was pregnant and near to her time. As the birth of their child approached, Ligdus told Telethusa that he wished for her two things: first, that the birth cause her no pain, and second, that the child be a boy. For if the child wasn’t a boy, he commanded Telethusa to put her to death. (Girls were too much trouble and weak, you see.) Then they both wept.

Crying herself to sleep, Telethusa dreamed. She dreamed of Isis. Accompanied by the entire Egyptian retinue, the Goddess came and spoke to Telethusa:

“O, you who belong to Me, forget your heavy cares and do not obey your husband. When Lucina [Roman Goddess of Childbirth] has eased the birth, whatever sex the child has, do not hesitate to raise it. I am the Goddess, Who, when prevailed upon, brings help and strength: you will have no cause to complain, that the Divinity you worshipped lacks gratitude.”

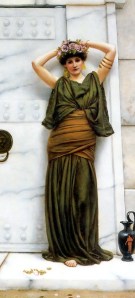

Isis comes to Telethusa in a dream

The child, of course, was a girl. Obeying the Goddess, Telethusa kept the baby and raised her as a boy. Her father even named her after his grandfather, Iphis. As Iphis was a name appropriate for either boy or girl, the mother secretly rejoiced. As Iphis grew, her features were such that she would have been considered beautiful whether a boy or a girl.

Time passed and Iphis’ father betrothed Iphis to the lovely Ianthe. The two met when quite young and were taught by the same teachers. From very early on, Iphis and Ianthe loved each other. For her part, Ianthe anticipated marriage to her beautiful Iphis. Iphis, on the other hand, as Ovid puts it, “loved one whom she despaired of being able to have, and this itself increased her passion, a girl on fire for a girl.”

Iphis wept, railed, and lamented her love for another girl. Iphis does not understand. She calls her passion monstrous and extreme and wants to wish it away—sort of. But eventually, Iphis pulls herself together and gives herself a good talking to. After all, she has almost everything she wants. Both her parents and Ianthe’s are happy with the match, Ianthe herself is happy with the match, and certainly Iphis is happy with the match (though she is afraid of the revelation of the wedding night). So she stops complaining and prays for the wedding to come.

Her mother Telethusa, on the other hand, feared what would happen when the two girls were wed. So she kept putting off the ceremony with a whole series of excuses. Yet finally, the wedding could be delayed no more. In desperation, Telethusa takes Iphis to the Temple of Isis. She throws herself upon the Goddess altar, crying and praying to Isis for help—for, after all, it was by the word of the Goddess Herself that Iphis lives!

Suddenly, the altar of the Goddess begins to shake. The temple doors tremble. The horns on the headdress of the statue of Isis shine like the moon and the rattling of sistra is heard throughout the temple. Heartened, mother and daughter take their leave of the Goddess. But as Telethusa turns to look at her daughter, she sees that Iphis now has a tanned, less ladylike, complexion, shorter hair, sharper features, and a longer, more masculine stride. Behold! Iphis is transformed into a boy.

In gratitude to Isis, mother and now, son, place a votive tablet in Her temple. And the next day, Iphis and Ianthe wed…and, we presume, lived happily ever after.

Ianthe and Iphis at the Temple of Isis

This story comes from a book called Metamorphoses in which Ovid tells the history of the world from Creation to Julius Caesar in a collection of myths about transformations of one kind or another. It was an immediate bestseller when first published and continues to exert influence and inspire art to this day. One of our best sources for over 250 classical myths, it was a major inspiration for Dante, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton.

The story illustrates a number of things about Our Goddess. First, it demonstrates Her soteriological function; Isis is well known as a Savior Goddess in the Roman period, and She saves Iphis and her mother in their time of need. The traditional Isian theme of dream visitation is part of the tale, too. In dream, Isis makes a promise to Telethusa, who “belongs to Her,” and She keeps the promise. Her saving nature, Her communication through dream, and Her ability to be there—in an immediate, even physical way—for Her devotees were all well-known aspects of the religion of classical Isis. But perhaps most importantly, the story shows the power of Isis’ magic.

In this tale, as from the beginning, Isis is the Goddess of Magic. And transformation is specifically one of the things She does. In one of the tales in the Egyptian myth cycle known as the Contendings of Horus and Set, for example, Isis transforms Herself into a beautiful young maiden, an old woman, and Her sacred raptor, the kite (a form She takes quite often, as a matter of fact). In this case, She transforms a girl into a boy; and so Iphis becomes a transgender Isiac.

We cannot know for certain what Ovid meant to impart by this tale and I don’t want to read too much into it. Yet I feel quite comfortable putting a modern interpretation on it and understanding in it the love of Isis for Her transgendered devotees. Modern priestesses, priests, and devotees of Isis come in all sexual orientations. We all hear the voice of the Goddess. We all feel Her strong wings. We all taste Her magic. She lives in all our hearts.

Metamorphoses sounds like a book I would like to own. If it inspired Dante, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton, it may have something to recommend itself. I am working towards some personal changes in my life right now. Love the timeliness of this.

You can find it online easily…the trick is finding an elegant translation. I paraphrased here because the translation I was looking at was kinda…meh.

Reblogged this on The Darkness in the Light.

I suspect this bit of Ovid also inspired some medieval French poets, including the one who wrote Le Roman du Silence; transformations by saints of girls into boys also occurs fairly often in Irish hagiography, so perhaps they got it from Ovid (and Isis, ultimately!) as well.

Love that idea! I’ll have to look into Le Roman du Silence. Thank you!

I can’t recall now how it ends, as it’s been about 12 years since I read it…but, there is this wonderful part where Silence witnesses a debate between “Nature” and “Nurture” over where gender comes from…for the 12th century CE, it’s rather socially advanced! Some modern medievalists have asked if it is too good to be true for gender studies and such, since it has only been known about widely for the last 40 years or so. In any case, it’s a fascinating and fun text!

Thank you so much for this – back when it was originally posted and now! I included a FB link today to this piece for Transgender Remembrance Day 2014.

Isis Bless and Blessed be!

Thank you for the link! Isis bless you as well.

Is

I was so amazed to learn this story! It’s funny how much I as a modern transmasc devotee of Isis can relate to this. Growing up, I was always a bit tomboyish, I found that I was attracted to women (which gave me a lot of trouble growing up in rural and very christian places), and then started experimenting with my gender identity later on. Since I started following Isis, I had the feeling that she was accepting of who I was, but it’s very comforting and healing (especially as someone who had to deal with religious queerphobia my whole childhood) to hear a story of Her loving and helping someone similar to me. Thank you!